Congratulations on your recent shortlisting for the Costa Poetry Award. This is a huge achievement, what does it mean to you and your work?

I think poets write basically because they want to engender some sort of emotional reaction in a reader. This might be making a reader laugh or, even better, moving them in a deeper way. Ultimately we want to make readers feel the way that our favourite poems make us feel – that’s what keeps us writing. A shortlisting for any award doesn’t increase the emotive power of your poems, but it does increase the number of people who your poems might reach. If the book’s involvement with the Costa Poetry Award means that one or two of the poems hit a couple more human hearts, that’s brilliant.

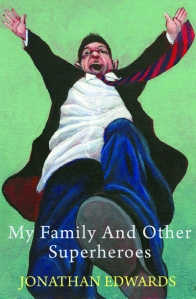

My Family and Other Superheroes is firmly set in Wales, what does it mean to you to be a Welsh poet?

Welshness is clearly really central to the book, particularly the second sequence of poems in the collection, beginning with ‘Anatomy,’ which passes through a number of Valleys village and town settings and takes on a number of issues which are important in Welsh history, such as Chartism or the drowning of Capel Celyn. Poets are at their best when they’re writing about what they love, of course, and you don’t have to look very hard in Wales at our landscape, or to spend much time with our people, before being inspired to write. Books about Welsh history, such as John Davies’s A History of Wales and Gwynfor Evans’s Land of My Fathers, were also important in forming the conception of national identity which is there in the poems.

Welshness is clearly really central to the book, particularly the second sequence of poems in the collection, beginning with ‘Anatomy,’ which passes through a number of Valleys village and town settings and takes on a number of issues which are important in Welsh history, such as Chartism or the drowning of Capel Celyn. Poets are at their best when they’re writing about what they love, of course, and you don’t have to look very hard in Wales at our landscape, or to spend much time with our people, before being inspired to write. Books about Welsh history, such as John Davies’s A History of Wales and Gwynfor Evans’s Land of My Fathers, were also important in forming the conception of national identity which is there in the poems.

At the same time, I sort of hope that by writing about Welshness I’m also trying to reach for something universal. A representative poem here is ‘Colliery Row’ which describes the experience of living in a Valleys terrace. In some ways the poem is specifically Welsh and tries to draw on the inheritance of Under Milk Wood and of RS Thomas poems such as ‘Village.’ But there are a number of other influences here. John Cooper Clarke’s poem ‘Beasley Street’ was very important, as was Douglas Dunn’s collection Terry Street, as was the classic story cycle of small town life, Winesburg, Ohio, by the American Sherwood Anderson. Can a poem like ‘Colliery Row’ say something about a terraced existence in Manchester or Glasgow? Can you get to the universal through the specific? These are questions for a reader to answer.

You’re a teacher, are your students inspired by your success and do you feel you have a hand in developing the next generation of poets?

I teach in a secondary school, and the daily experience of working with teenagers means that any notion of inspiring students needs to be taken with a large fistful of salt, if you’re going to get anywhere! Like any teacher I try my best, and with English we’re lucky because getting children and teenagers involved in writing is great fun and can unlock something they really enjoy. We’re also really lucky in Wales to have the level of support we have from organisations like Literature Wales. Their Writing Squads initiative, for example, which allows children and teenagers from a wide range of backgrounds access to monthly workshops with established writers, is an incredible thing, and their activities in connection with Dylan Thomas’s centenary have done a great deal for young writers. ‘Dylan’s Great Poem,’ for example, which invited writers aged 7-25 to submit lines for inclusion in an epic poem edited by Owen Sheers, was easily one of the best things of my teaching year.

The other thing I’d like to mention in terms of the next generation of Welsh poets is the Terry Hetherington Award and its companion annual anthology of new Welsh writers, Cheval, which is published by Parthian. The award is supporting an emerging and exciting generation of new Welsh and Wales-based writers, including Tyler Keevil, Jemma L. King, Anna Lewis, Georgia Carys Williams, Mao Oliver-Semenov and a number of others. The next deadline for the award is this January, and I would urge anyone under thirty in Wales who is serious about writing to enter – it really is an incredible thing.

What authors or poets are you inspired by?

I tend to enjoy the work of poets who are able to combine humour and accessibility with something serious or emotive. Jo Shapcott and Deryn Rees-Jones are important poets for me, particularly in terms of the way they handle the surreal in poems such as ‘Superman Sounds Depressed’ and ‘Lovesong to Captain James T. Kirk.’ A number of American poets who write in a similar style have also been important. David Wojahn, for example, for his use of pop culture, has been an important influence, particularly in his extraordinary sonnet sequence ‘Mystery Train,’ and Charles Simic, James Tate and Thomas Lux are poets whose work I keep returning to. For their writing about family, Greta Stoddart and Tom French are writers I love, while the music and forms of Simon Armitage and Alan Gillis have been important in the development of my voice.

Who do you think are Welsh poets or authors to look out for in the future?

I’ll mention two people here, and interestingly they’re both prose writers. Firstly, Thomas Morris comes from Caerphilly and is editor of the excellent Dublin literary journal The Stinging Fly. His first collection of stories will appear from Faber next year and, for my money, is going to do something extraordinary in terms of the Welsh literary scene, though it will of course be appreciated more widely too. Tom’s book being placed with Faber is fitting as in some ways the work I’ve seen from him has something in common with DBC Pierre – they share a certain comic vision, though arguably Tom is a warmer writer, using the comedy to get to a stronger emotional punch. It’s that sort of thing – getting to the emotive through the comic – that I’ve always tried to hit in my writing, so I always have endless respect for those who pull that off.

For the same reason, I love the work of Lowri Llewelyn-Astley, from North Wales. Lowri was winner of the Terry Hetherington Award in 2012 and her short story, ‘Blue Smarties,’ from Cheval 6, is one of the most exciting things I have seen from a Welsh writer in a very long time. If she is able to sustain the comic brio, utterly distinctive voice and emotive power of that story over a complete collection or across a novel, she is likely to be one of Welsh literature’s greatest assets in the coming decades.

You’re active in the contemporary Welsh poetry scene, participating in open-mic nights and festivals, do you feel that the local creative writing world is something to be proud of?

Yes. The best thing about the collection coming out, really, has been the amazing people I’ve met as I’ve toured the book around Wales this past six months. From Cardigan to Cardiff, Llandrindod to Llandovery, there are people with incredible energy putting on literature events for their local community. Sometimes as a poet, writing in a room and dropping your words every few months into the blackness of the postbox, you can feel as though that blackness is exactly what you’re dropping your words into. Not so. Praise be to the people hiring the back rooms of pubs, putting up marquees, borrowing their brothers’ friends’ guitar amps for poets to read into. These are acts of love.

At the same time, though, this. I’ve just got back from the Aldeburgh Poetry Festival which is, very easily, the most impressive poetry event I’ve ever seen. The level of professionalism, the size and enthusiasm of the audiences, the way the three days bring together so many people who love poetry. Why on earth haven’t we got something like this in Wales? Our reputation across the world as a land of poets is unparalleled, so we deserve – no, we have an obligation to provide – a huge annual event, a celebration of international poets. The Aberystwyth International Poetry Festival? The Cardiff International Poetry Festival? With the energy that’s out there, spread around Wales, if we all came together…

If you could give one piece of advice to budding poets, what would it be?

The best piece of advice I ever got was from Hugo Williams, which I’ll paraphrase here – probably inaccurately, but it’s the way I’ve internalised it. All you can do with poetry, he said, is to decide to stick with it, to keep writing a poem every month or so. You can’t, he said, do anything about the quality of what you write. It’s incredibly liberating advice, that. Poetry is incredibly, incredibly competitive and it’s advice like that which keeps you going when things get tough. You read and write, you read and write, you read and write. You never give up. That’s all.

And lastly, what’s next for you?

I’m currently planning to work on three sequences of poems. One draws on Phil Stead’s incredible history of Welsh football, Red Dragons. Another aims to expand on the poem ‘Capel Celyn’ from my first collection – I’d like to write a sequence about the experience of people from the area. A third aims to work loosely with the ideas of romantic love which are present in Shakespeare’s sonnets. The way I work, though, is to write innumerable quantities of poems in such vague directions, before boiling them down into a carefully edited highlights. There’s always a large gap between my intention and the poems, which if they’re worth anything will do exactly what the hell they please. Long may that continue.

Thank you, Jonathan! If you’d like to buy Jonathan’s debut poetry collection My Family and Other Superheroes, you can find it here.